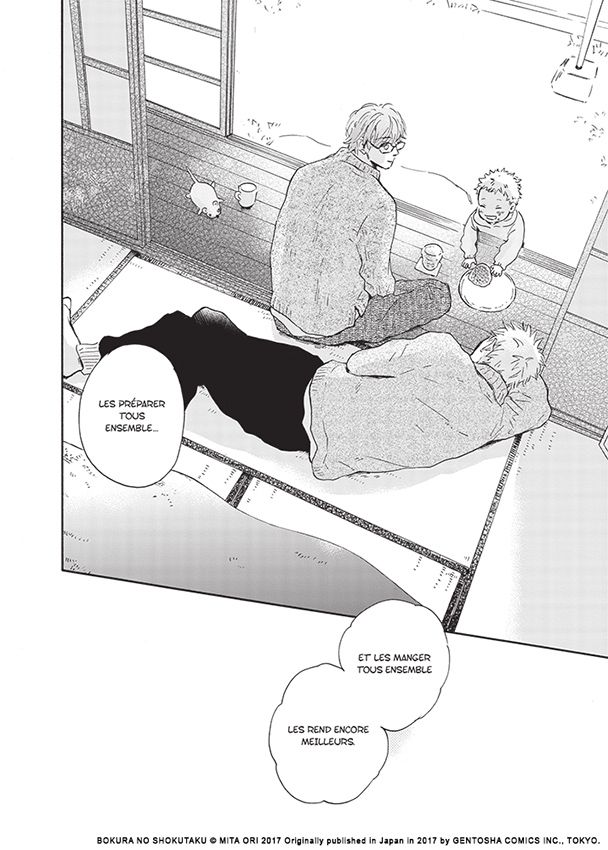

For the first time since he was a very small child, Yutaka’s loneliness has abated. No one in this family of men is a particularly good cook, but Yutaka finds, as he emerges from his food-based fears, that the quality of the food matters much less than the quality of the company. Surprising himself, Yutaka agrees, thus kickstarting a warm relationship with the brothers and their artist father.

Yutaka thinks nothing of the strange encounter until the pair of brothers resurface a few days later, and Minoru asks Yutaka if he could teach him how to make the onigiri about which Tane will not stop raving. Puzzled by the interaction, Yutaka nevertheless shares his food with the toddler until the boy’s much older brother, Minoru, fetches him and scolds him for wandering away. It is while he is eating one of these humble meals on a bench in the park that he meets Tane, a little boy whose hunger leads him to beg for some of Yutaka’s large onigiri. He is a good cook, but he only makes himself homemade onigiri, getting the bulk of his nutrition through pre-cooked convenience store meals. His coworkers have stopped inviting him out for food or drinks because he always turns them down, and this lack of socializing has led him to have a lonely life. However, Yutaka, the protagonist of Mita Ori’s Our Dining Table, has difficulties eating around others, stemming from childhood trauma caused by his adoptive siblings.

Food and the rituals that surround it are a central part of every culture, from regular everyday meals to offerings to our deceased. We go on dinner dates, run out for a coffee break in pairs, swing by the bar after work, and hopefully sit down to dinner with our families or other loved ones. All the world over, people find themselves connecting over food.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)